Background

Zero-knowledge proofs

Recently, a set of cryptographic primitives called zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) agitated the world of public blockchains and distributed ledgers. ZKPs came up first as a solution to privacy issues but they have lately also stood up as a perfect solution to scalability issues. As a result, these cryptographic proofs have become very attractive tools to the blockchain community, and the most efficient algorithms have already been deployed and integrated in several applications.

A zero-knowledge proof is a protocol that enables one party, called the prover, to convince another, the verifier, that a statement is true without revealing any information beyond the veracity of the statement. For example, a prover can create proofs for statements like the following:

- "I know the private key that corresponds to this public key" : in this case, the proof would not reveal any information about the private key.

- "I know a private key that corresponds to a public key from this list" : as before, the proof would not reveal information about the private key but in this case, the associated public key would also remain private.

- "I know the preimage of this hash value" : in this case, the proof would show that the prover knows the preimage but it would not reveal any information about the value of that preimage.

- "This is the hash of a blockchain block that does not produce negative balances" : in this case, the proof would not reveal any information about the amount, origin or destination of the transactions included in the block.

Non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs (NIZK) proofs are a particular type of zero-knowledge proofs in which the prover can generate the proof without interaction with the verifier. NIZK protocols are very suitable for Ethereum blockchain applications, because they allow a smart contract to act as a verifier. This way, anyone can generate a proof and send it as part of a transaction to the smart contract, which can perform some action depending on whether the proof is valid or not.

In this context, the most preferable NIZK proofs are zk-SNARK proofs (Zero-knowledge Succinct Non Interactive ARgument of Knowledge), a set of non-interactive zero-knowledge protocols that have succinct proof size and sublinear verification time. The importance of these protocols is double: on the one hand, they help improve privacy guarantees, but on the other, their small proof size has been used in scalability solutions.

Arithmetic circuits

Like most ZKPs, zk-SNARKs permit proving computational statements, but they cannot be applied to the computational problem directly, the statement first needs to be converted into the right form. Specifically, zk-SNARKs require the computational statement to be modeled with an arithmetic circuit. Although it may not always be obvious how to do this conversion, most computational problems we care about can easily be converted into arithmetic circuits.

An F_p-arithmetic circuit is a circuit consisting of set of wires that carry values from the field F_p and connect them to addition and multiplication gates modulo p.

👉 Remember that given a prime number p, the finite field F_p consists of the set of numbers {0,...,p-1}on which we can add and multiply these numbers modulo p.

For example, the finite field F_7 consists of the set of numbers {0,...,6}on which we can add and multiply numbers modulo 7. An easy way to understand how operating modulo 7 works, is to think of a clock of 7 hours in which we do not care about how many times the hands have turned the clock, only what time they mark. In other words, we only care about the remainder of dividing by 7. For instance:

15 modulo 7 = 1, since15 = 7 + 7 + 17 modulo 7 = 04*3 modulo 7 = 5, since4*3 = 12 = 7 + 5

Signals of a circuit

So, an arithmetic circuit takes some input signals that are values between 0,...,p-1 and performs additions and multiplications between them modulo the prime p. The output of every addition and multiplication gate is considered an intermediate signal, except for the last gate of the circuit, the output of which is the output signal of the circuit.

To generate and validate zk-SNARK proofs in Ethereum, we need to work with F_p-arithmetic circuits, taking the prime:

p = 21888242871839275222246405745257275088548364400416034343698204186575808495617

👉 This prime p is the order of the scalar field of the BN254 curve (also known as the ALT_BN128 curve) as defined in EIP 196.

👉 Circom 2.0.6 introduces two new prime numbers to work with, namely the order of the scalar field of the BLS12-381

52435875175126190479447740508185965837690552500527637822603658699938581184513

and the goldilocks prime 18446744069414584321, originally used in Plonky2.

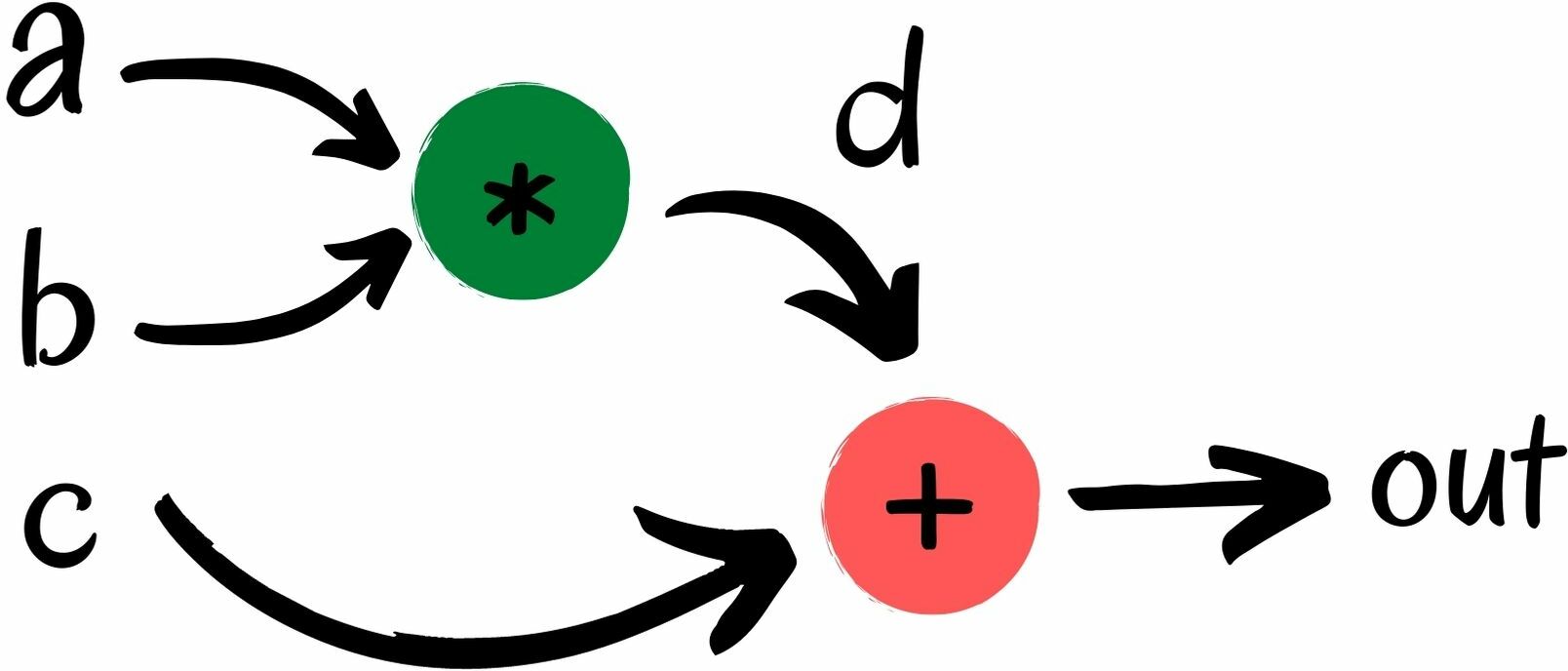

In the figure below, we have defined an F_7-arithmetic circuit that performs the operation: out = a*b + c. The circuit has 5 signals: the signals a, b and c are input signals, d is an intermediate signal and theout signal is the output of the circuit.

In order to use zk-SNARK protocols, we need to describe the relation between signals as a system of equations that relate variables with gates. From now on, the equations that describe the circuit will be called constraints, and you can think of them as conditions that signals of that circuit must satisfy.

Rank-1 constraint system

If we have an arithmetic circuit with signals s_1,...,s_n, then we define a constraint as an equation of the following form:

(a_1*s_1 + ... + a_n*s_n) * (b_1*s_1 + ... + b_n*s_n) + (c_1*s_1 + ... + c_n*s_n) = 0

Note that constraints must be quadratic, linear or constant equations, and sometimes, by doing small modifications (like a change of variable or gathering two constraints), it is possible to reduce the number of constraints or variables. In general, circuits will have several constraints (typically, one per multiplicative gate). The set of constraints describing the circuit is called rank-1 constraint system (R1CS):

(a_11*s_1 + ... + a_1n*s_n)*(b_11*s_1 + ... + b_1n*s_n) + (c_11*s_1 + ... + c_1n*s_n) = 0

(a_21*s_1 + ... + a_2n*s_n)*(b_21*s_1 + ... + b_2n*s_n) + (c_21*s_1 + ... + c_1n*s_n) = 0

(a_31*s_1 + ... + a_3n*s_n)*(b_31*s_1 + ... + b_3n*s_n) + (c_31*s_1 + ... + c_1n*s_n) = 0

...

...

(a_m1*s_1 + ... + a_mn*s_n)*(b_m1*s_1 + ... + b_mn*s_n) + (c_m1*s_1 + ... + c_mn*s_n) = 0

Remember that operations inside the circuit are performed modulo a certain prime p. So, all equations above are defined modulo p.

In the previous example, the R1CS of our circuit consists of the following two equations:

d = a*b modulo 7out = d+c modulo 7

In this case, by replacing directly the variable d, we can gather the two equations into a single one:

out = a*b + c modulo 7

The nice thing about circuits, is that although most zero-knowledge protocols have an inherent complexity that can be overwhelming for many developers, the design of arithmetic circuits is clear and neat.

👉 With circom, you design your own circuits with your own constraints, and the compiler outputs the R1CS representation that you will need for your zero-knowledge proof.

Zero-knowledge permits proving circuit satisfiability. What this means is, that you can prove that you know a set of signals that satisfy the circuit, or in other words, that you know a solution to the R1CS. This set of signals is called the witness.

Witness

Given a set of inputs, the calculation of the intermediate and output signals is pretty straightforward. So, given any set of inputs, we can always calculate the rest of the signals. So, why should we talk about circuit satisfiability? The key aspect of zero-knowledge proofs is that it allows you to compute these circuits without revealing information about the signals.

For instance, imagine that in the previous circuit, the input a is a private key and the input b is the corresponding public key. You may be okay with revealing b but you certainly do not want to reveal a. If we define a as a private input, b, c as public inputs and out as a public output, with zero-knowledge we are able to prove, without revealing its value, that we know a private input a such that, for certain public values b, c and out, the equation a*b + c = out mod 7 holds.

Note that we could easily deduce the value of

aby isolating it from the other signals. It is important to design circuits that keep the privacy of the private inputs and prevent deducing them from the R1CS.

An assignment of the signals is called a witness. For example, {a = 2, b = 6, c = -1, out = 4} would be a valid witness for the circuit. The assignment {a = 1, b = 2, c = 1, out = 0} would not be a valid witness, since it does not satisfy the equation a*b + c = out mod 7.

Summary

In summary, zk-SNARK proofs are an specific type of zero-knowledge proofs that allow you to prove that you know a set of signals (witness) that match all the constraints of a circuit without revealing any of the signals except the public inputs and the outputs.